7 ways policymakers should respond to the cost of living crisis

To win an economy that works for people and planet, we need a new approach to inflation

The UK’s cost of living crisis is taking its toll, particularly on low-income households. The anticipated change in the energy price cap in April is set to plunge an additional four million families into ‘fuel stress’, where 10% or more of their income is spent on energy. As the latest headline inflation figure hits 4.8%, the Bank of England is set to continue raising its base interest rate, increasing the cost of borrowing in an effort to exert downward pressure on prices by reducing demand for goods and services. But this will fail to address current sources of inflation, and could even exacerbate the cost of living crisis by lowering future output and employment. A search for alternative solutions is generating much-needed debate about how we should think about, measure and navigate price changes.

As we lurch from one crisis to the next, misguided monetarist views that treat inflation as the result of excess demand driven by growth in the money supply are more dangerous than ever. Prescribing higher interest rates and lower government spending threatens the prospects for achieving a sustainable and socially just future. Senator Joe Manchin’s use of rising inflation to justify quashing Joe Biden’s ‘Build Back Better’ bill – intended to tackle climate change, create jobs, and improve welfare and social services – is a case in point. If fallacious arguments about prices are left unchallenged, they will contribute to an inadequate response to the cost of living crunch, and continue to undermine much-needed efforts to invest in social safety nets and green infrastructure.

So as inflation rears its head, how should we respond? There are seven key points that should underpin new approaches to thinking about and managing price hikes.

1) Headline inflation figures don’t tell us much about the economy

The Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) headline inflation figure – the Consumer Price Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH) – is a weighted average of price changes across a ‘representative’ basket of approximately 700 goods and services. Tracking and presenting price changes of these items is a vital job, which ONS statisticians carry out laudably, but headline inflation figures alone don’t tell us specifically which prices are changing, in what direction, by how much, for what reasons, or to what effect.

This is important because prices don’t move up and down in perfect synchrony, but rather tend to vary wildly across sectors. For example, in the early stages of COVID-19, prices plunged for many recreational activities, package holidays and meals out, but skyrocketed for pandemic-related essentials such as masks, rubber gloves, disinfectants and many food items. In addition to sectoral variations, prices also move in divergent ways within sectors and even within specific categories of goods and services, often in ways that even the ONS’ vast dataset of 700 items does not capture. A rather jarring example of such a variation: funeral service prices on average decreased in 2021, but the price of cremations without a service – the cheapest type of funeral – rose by 6%.

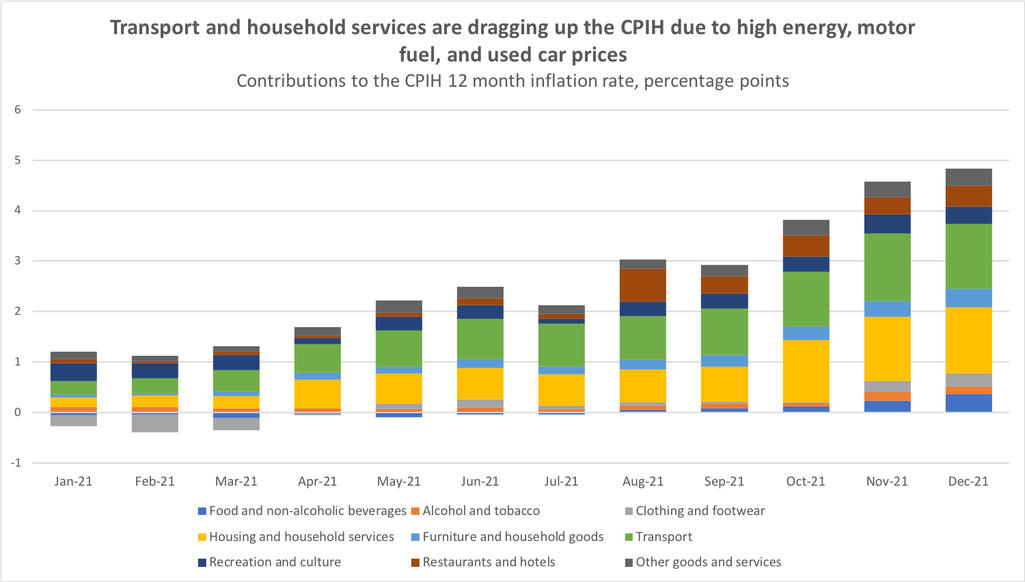

Due to these divergent changes, big price changes in individual sectors or categories of goods can significantly pull the headline inflation figure in one direction or another. For example, in August 2021, used cars and the end of the UK government’s ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme the previous year accounted for a sixth of the 3% CPIH figure. Although price rises have become slightly more broad-based recently, a full third of December’s 4.8% CPIH figure came down to motor fuels, used cars and household energy.

Even if all goods and services were displaying similar price increases, making the index more reflective of a ‘general’ rise in prices, one would still have to look beneath the headline inflation rate to grasp that dynamic.

Ultimately, CPIH inflation is just one inflation rate, based on questionable concepts of a ‘representative’ basket of goods, a ‘typical’ spending pattern, and an ‘average’ household. In practice, there are as many different inflation rates as there are patterns of consumption. The idea of one true inflation rate for the whole population is not all that meaningful or useful for informing policy. To understand how price changes are affecting different households and what an effective policy response might look like, it’s necessary to look beneath and beyond existing headline inflation figures, as the ONS itself recently acknowledged.

2) Increases in the prices of essential goods and services hit the poorest the hardest

While the distributional consequences of price increases can be complex and varied, one constant is that low-income households are far less able to absorb increases in the prices of essentials, such as energy and cheap food items. This should be obvious, but multiple economics journalists seem to be missing this basic point, claiming that “higher earners will be worst hit by rocketing inflation” and that the story of recent inflation is “one of shared pain rather than concentrated pain among the poorest”. In reality, there’s no doubt that those struggling to pay rent and put food on the table are feeling the surge in energy bills and cheap food items far more acutely than wealthy households.

Furthermore, essential items that make up the vast majority of poorer households’ budgets are highly ‘inelastic’, meaning that their consumption cannot be easily substituted or deferred to a later date. Simply put, people need to eat, stay housed, and use energy and water on a daily basis. On the other hand, the purchase of non-essential items, which feature to a greater extent in wealthier households’ consumption baskets, can be more easily substituted or deferred. Buying cheaper wine, staying in for dinner instead of eating out, or delaying the purchase of the latest iPhone may be irritating and inconvenient to some consumers, but it won’t put their lives at risk or threaten their basic human dignity.

3) Price changes are driven by many economic and political factors

Even central bankers, whose main job is to target a given inflation rate (usually 2%), are starting to admit that they have no reliable theory of how ‘inflation’ works. Attempts to develop simple models of inflation have papered over the fact that companies’ price-setting behaviour is affected by a wide range of factors often entirely unrelated to the money supply, such as exploitative pricing by companies, supply chain disruptions, and geopolitical tensions.

Looking into the key items pushing up recent CPIH figures offers a good example of how myriad economic and political factors feed into price changes. Energy price pressures since late 2021 have resulted from Britain’s reliance on depleted European gas stocks, high demand for liquefied natural gas in Asia and Latin America, and a drop in gas supplies from Russia. Heightening tensions between Ukraine and Russia could exacerbate this situation. Meanwhile the price surge in second-hand cars, another significant contributor to CPIH inflation, has largely been caused by a shortage in microchips preventing the production of new cars earlier in the pandemic, meaning there are fewer second-hand cars on the market today. Other drivers of recent price rises include COVID and Brexit-related worker shortages, disruptions in the global shipping network resulting from the shuttering of factories followed by changes in patterns of consumption, and corporate profiteering as the likes of BP and Shell have grown their profit margins while ordinary families struggle to pay their energy bills.

Monetarist views that focus on high government spending and loose monetary policy as drivers of inflation ignore all of these far more important supply-side dynamics. This failing results in regressive policy outcomes that aim to reduce consumer demand by increasing unemployment and making people poorer. Understanding what forces are driving particular price changes is a necessary prerequisite for designing an effective policy response that minimises, and protects the most vulnerable from, increases in the cost of living.

Related story

4) Higher employment and wages don’t necessarily generate price rises

Few terms have been as influential in central banking as the ‘non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment’ (NAIRU), the lowest unemployment rate at which inflation is meant to remain stable. The theory behind this concept goes as follows: if unemployment is low, attracting and retaining workers requires employers to offer higher wages, the costs of which they subsequently pass onto consumers in the form of higher prices. Workers then demand even higher wages due to the rise in the cost of living, and, because the labour market is tight, employers give into these demands for higher wages, which prompts further price rises, and so on and so forth, resulting in a so-called ‘wage-price spiral’.

But the existence of a NAIRU is not borne out in the data, which shows no observable inverse relationship between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate. Furthermore, if it were true that the costs of higher wages were always passed on to consumers, the distribution of total national income between labour and capital would always remain the same – workers could never improve their situation relative to owners of capital. Historically, this has also not been the case. In reality, workers’ share of the economic pie increased over time in the post-World War Two era, until it changed course and went into secular decline from the 1980s onwards.

This doesn’t mean that a wage-price spiral isn’t possible, but it requires three main conditions: (i) a strong labour movement, such that workers can mobilise to win higher wages; (ii) a high degree of market concentration, meaning that companies have the power to hike prices without losing customers to competitors; and (iii) policymakers that allow market concentration to persist and fail to employ adequate tools to minimise price increases. Currently, we don’t have a strong labour movement, yet we do have small numbers of gargantuan companies dominating sectors such as energy, food, car manufacturing, technology, and banking, while policymakers turn a blind eye to abuses of corporate power. Countering fears of a ‘wage-price spiral’ should therefore focus on tackling excessive market power.

5) Environmental breakdown is ushering in a new era of intensified price volatility

Climate change and ecological breakdown are hurtling humanity into an era of profound instability and uncertainty in which prices will certainly not go unscathed. Even the pandemic-related inflationary pressures we’re experiencing right now can be attributed to environmental destruction, given that the emergence of COVID-19 was linked to the exploitation and degradation of natural ecosystems. Smaller-scale climate-related physical shocks are also increasingly affecting prices, as was recently demonstrated by pasta shortages due to a poor wheat harvest following record temperatures and droughts in Canada. Meanwhile, our dependence on fossil fuels is leaving us exposed to ongoing energy price hikes.

All current supply-side drivers of price pressures, such as shipping disruptions and geopolitical tensions, will be severely exacerbated as environmental breakdown continues to intensify. On the other hand, climate and nature-related shocks could dampen demand, countering supply-side drivers of inflation, but this would come at a major cost to human wellbeing and life. Moving forward, environmental policy should also be seen as inflation policy. If we fail to tackle the climate crisis and ecological collapse, price changes will be far from the worst of our worries, but they’ll compound the instability and the suffering.

When it comes to climate change, central banks have mostly focused on implications for the stability of the financial system, but they’re increasingly also considering how it relates to their price stability mandates. The Bank of England must now recognise that if it really wants to meet its objective for price stability over the medium term, the best course of action is to direct credit away from volatile fossil fuels and towards a stable source of low-cost renewable energy.

6) A wide range of tools is necessary to manage inflation and protect the vulnerable

Responses to inflation should view interest rate hikes as, at best, a last resort, and only if there is strong evidence of broad-based inflation driven by unusually high levels of demand. Barring that scenario, there’s a multitude of other tools and strategies on the table to address price increases. In the current environment, policymakers should consider a range of immediate, short-term measures to ease the cost of living squeeze, as well as more long-term structural changes to prevent a potential inflationary spiral.

In the short term, policymakers should focus on:

- Preventing excessively high pricing, for instance by further capping energy prices. Public ownership in key sectors such as energy, food and pharmaceuticals would also minimise harmful exploitative pricing and allow for new business models in line with a green and fair industrial strategy.

- Protecting the poorest by upgrading benefits or providing direct cash transfers to distressed households’ bank accounts, shielding them from price increases that are deemed inevitable in the short term due to rapidly rising costs.

In the long term, the focus should be on:

- Increasing productive capacity for environmentally friendly substitutes by stepping up public investment in, and redirecting credit towards, green projects and infrastructure. This would make consumers less dependent on, and therefore less exposed to, potential further increases in the cost of cars and dirty energy.

- Breaking excessive market power via stronger antitrust regulation, reducing firms’ ability to engage in exploitative pricing and lessening the need for price caps.

- Dampening demand among those who can most afford it, for example by taxing the wealthy, which would also help to avert climate breakdown and its associated price volatility.

There’s no single silver bullet for managing price rises, so all of these options and more should be explored in further depth if we’re serious about navigating and managing price increases in a way that supports people and planet. Expecting the base interest rate to do all the work is foolish, counter-productive and dangerous for the most vulnerable in society.

7) Multiple institutions are needed to implement these tools

We can’t keep placing all the responsibility for managing inflation on central banks. Instead, given that headline inflation figures aren’t very informative and most of the tools discussed above fall well outside the jurisdiction of monetary policymaking, we must challenge the very concept of ‘inflation targeting’ by central banks. History is replete with examples of monetary and financial authorities acting in support of industrial development rather than following narrow price stability mandates.

History also offers lessons on how other public institutions can be useful in combating price increases. For instance, President Roosevelt established the Office for Price Administration in 1941 and staffed it with 250,000 employees tasked with identifying and addressing sources of inflationary pressures. And in the UK, where ‘fiscal policy, propaganda, subsidy, legislation, and administrative regulation’ were all used as “weapons in British price control efforts” during World War Two, several ministries across government were responsible for monitoring and managing particular price changes.

It’s time to rethink the institutional arrangements dominating modern economic policy. Closer coordination between government departments and the Bank of England is urgently needed to control inflation and drive the transition to a fair, sustainable economy.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.